These two exercises are all about diving into python and getting our hands dirty. The first is getting a program to ask for user input. The second is to make the coolest Turtle program you can and post it to our blog. There's nothing to turn in for the first exercise. I'll walk thru the first one in class and as much of the second one as I can. For this exercise, practice knowing only what you need to solve the problem- don't be worried if you don't understand everything. Next class we'll back up and examine some of the concepts we're glossing over.

Custom Input for Turtles

In the ActiveCode Example 2, there's an example that introduces background colors. It suggests we extend the program to accept user input. Let's do that now.

When you're done with this part of the exercise you'll have a program that:

- prompts the user for Tess's color and makes her that color

- prompts the user for a background color and makes it that color

- prompts the user for Tess's pen size and makes her pen that size

To prompt the user for input we'll need Python's raw_input() function. We haven't learned about functions yet, but since we're diving in we're just going to use it and see what happens.

Read up a little on some of the results from a quick Google search:

- Python's official docs for

raw_input - Stack overflow question

Like much of the documentation we'll find in programming, these imply or depend on a lot of background knowledge you may or may not have. Push on even if you don't understand and see what happens in the code! I'll mention a few things that might help.

raw_input gets a value, and we have to store it somewhere to use it in our program. That's why in the example on Stack Overflow there's an assignment of the statement to a variable. For example, we might store the result like this:

tess_color = raw_input("What color should Tess be?")

This will cause a window to pop up asking "What color should Tess be?" and save the user input into the variable. We can then use the tess_color variable later, in place of something like "red" or etc.

Using this information, knock out the three components of the exercise above.

Turtlehacking

Now that we know a little about how to make Turtles do cool stuff, let's hack them!

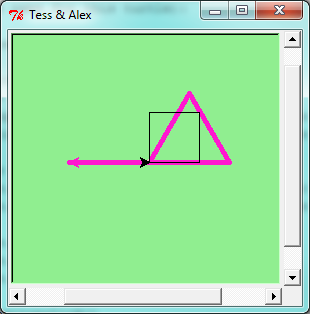

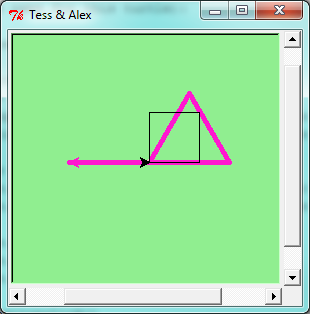

The Turtle library is code that someone else wrote for us. You can see the full extent of that code here. The Textbook reading we had uses only some of this library or module's functionality. We'll learn some more about this functionality, make some pretty pictures, and post our results on the blog. At the end of this exercise you should have:

- Some Turtle code that, when run on the interactive python site (i.e. our textbook) produces an awesome picture. The more awesome the better. The more use of the Turtle module's special abilies the better.

- The picture itself, taken as a screenshot.

- A post to our class blog that includes the code

Let's get started!

Writing Turtle code.

Our textbook has several interactive boxes that contain Turtle code. Here's an example:

import turtle # allows us to use the turtles library

wn = turtle.Screen() # creates a graphics window

alex = turtle.Turtle() # create a turtle named alex

alex.forward(150) # tell alex to move forward by 150 units

alex.left(90) # turn by 90 degrees

alex.forward(75) # complete the second side of a rectangle

Find one of the interactive boxes that strikes your fancy and start playing around with it until it looks awesome. Note that if you sign up for a free account you'll be able to save and load your custom code.

How to make it awesome? Well, you can Google for awesome Python Turtle examples. You might also stumble across the Turtle module's documentation. This may seem a little confusing but a little basic vocab should help. "Methods" are things you can do to an object. So in the code above alex is a Turtle object (the code alex = turtle.Turtle() makes him). The .forward(150) and otherr things hanging off of alex are methods. With that information, see what other things you can make turtle objects do.

The name alex above could be another set of letters. As long as we tell Python it's a Turtle object these methods will be available.

Sharing your work

Programmers often need or want to share their work with others. We're going to do that by making a jekyll post with our code, a screenshot of our picture, and any thoughts or reflections we have on the experience.

First you need a header:

--- layout: post author: elliott title: Elliott's Turtle Exercise ---

Then we'll want to display code. The cool grey boxes above come from telling Jekyll that we're about to write code using backticks: `

```

import turtle

wn = turtle.Screen()

wn.bgcolor("lightgreen")

tess = turtle.Turtle()

tess.color("blue")

tess.pensize(3)

tess.forward(50)

tess.left(120)

tess.forward(50)

wn.exitonclick()

```

Finally, we need to embed an image. Using Markdown, we do this thus:

So the code above would look like this when rendered by Jekyll:

import turtle

wn = turtle.Screen()

wn.bgcolor("lightgreen")

tess = turtle.Turtle()

tess.color("blue")

tess.pensize(3)

tess.forward(50)

tess.left(120)

tess.forward(50)

wn.exitonclick()

Thoughts about the exercise

When submitting exercises, it's always awesomer to include reflections, roadblocks you ran into, or things you thought were cool. Always include links to example code if you use or are heavily influnced by someone else's work. They don't have to be long, but the best ones give me a sense of what you did and why. Here's a post from last class that does a good job of this: Sarah's post from Fall 2013

Going deeper

Think the above is easy? Try your hand at writing and calling functions. We'll get to these later but an example from our very own Grant McLendon might help inspire you: Grant's Turtle post form Fall 2013